On the evening of September 11, 2020, I joined my cohort of the Louisiana Master Naturalist of Greater New Orleans for a mosquito-filled evening on the Coquette Trail of the Barataria Unit of Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve. Being after hours, we had the place to ourselves, save the countless organisms who call this ecosystem home. The following reflections describe my knowledge gained about the bottomland hardwood and swamp ecosystems in the park.

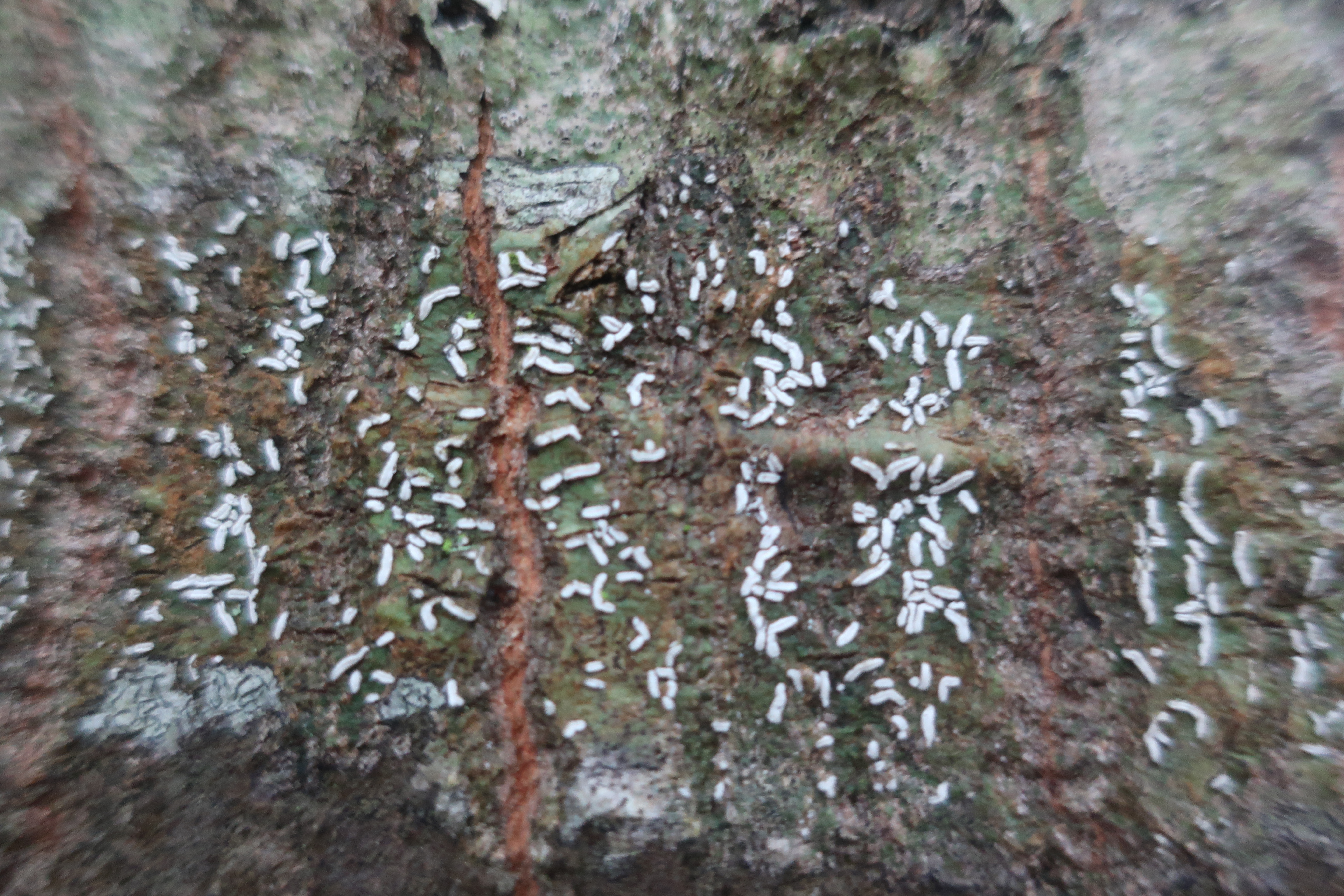

We almost immediately stopped at a spot on the trail where we could view a typical swamp habitat, complete with expected Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) and Tupelo gum (Nyssa aquatica). We learned how to tell the two apart, since they are often found together, and I have since found myself educating everyone I meet on their differences (e.g. fluted-ness, leaf type, bark color). Upon closer inspection of a Water oak (Quercus nigra), we found curious straight rows of holes in the bark. We learned that this was the work of the Yellow-bellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius), a striking bird which spends the non-breeding part of its life in warmer climates. They feed on the sap of trees, using their beaks to drill holes at two depths in order to access the sap within. Other birds such as hummingbirds often come behind and sneak sips of leftover sap. On this same oak, we also found what looked like tiny chromosomes in two bands around the trunk. These turned out to be a type of lichen, which occur via a mutualistic relationship between algae and fungi. Many trees showed signs of decay, and some had succumbed to the life cycle of the forest and were being decomposed by fungi only to contribute to the growth of epiphytes (plants which grow on plants) or habitat for critters. This ecosystem service provided by fungi allows for successional growth of the forest, and we could see this in practice as trees of all ages surrounded us.

Once the moon rose, the Bronze Frog (Lithobates clamitans) and all its amphibian friends came out to feed and play. At night, we had to be careful not to get caught in the massive yellow webs of the Golden Silk orb weaver (Nephila), left for months above the trees and among the dwarf palmettos in order to catch anything which might become a meal. We learned that this species (and many other spiders) are great examples of sexual dimorphism, where the male and female are different sizes. All of the large impressive spiders responsible for the large yellow-silked webs are females, and if you look closely for a tiny spider next to the female, you might find the male waiting for an opportunity to impregnate his mate. He often waits until she is preoccupied and distracted with a meal, in fact. These webs are full of interesting relationships like this, including a clepto parasitic one; a tiny dew drop spider (Argyrodes) waiting for a web-catch too small for the orb weaver to bother, such a mosquito or gnat. We wondered how to define this relationship: was it mutualistic with the dew drop “cleaning” the web for the orb weaver? Each of these night creatures had established itself in the ecosystem of the swamp, sympatric but allotopic in many cases. They shared the space and understood that the frogs found food closer to the ground and on the leaves of the palmettos, while the spiders occupied the spaces between.

As we stood on the darkened platform listening to the occasional frog call of the swamp, we could see in the distance the silhouette of a massive Bald cypress tree – known affectionately as the “mammoth” – which somehow survived the logging of the 1800s. We rely on trees of many kinds for our timber needs, and refer to this as a provisional ecosystem service. The Cypress swamp was logged almost completely as European settlers decided to make southern Louisiana their home. From the 1700s until the mid-20th century, these culturally important trees provided the structure from many homes and other infrastructure. Society eventually understood the importance of these particular trees to the ecosystem and moved towards growing timber on plantation farms instead. Still, with the few Cypress that were spared, we can imagine what a magical place the original Cypress swamp would have been.

For the final portion of our workshop, we made our way to the parking lot to watch bats work their sky routes above us. As he attracted bugs to a large flashlight for bats to swoop and eat, Dr. Craig Hood, local mammalian expert, educated us on all-things-bats. Interestingly, we learned how the tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus) hibernates in the caves of the northern United States, but does not have a need – or habitat – to do so here in southeastern Louisiana. On the rare night when temperatures might reach the 20s, the tri-colored bat enters the torpor state, meaning their systems’ need to expend energy decreases. Southern tri-colored bats have the ability to hibernate in their DNA (like their northern cousins), but they have adapted to these warmer climates and do not need to tap into that hibernating instinct. They have instead learned where there are sources of food at all times of the year, and rely on these spaces for sustenance. These bats, and all of the other species which rely on insects for food, are being threatened by the human need to rid our world of those bugs, especially mosquitoes. As we spray for mosquitos, every other thing is sprayed too, and nothing can escape this deadly poison. Bats are not threatened by any of the other species in their environments – not even the large Barred owl (Strix varia) whose far-off hoot made all our heads turn; the bats need only worry about diseases and a loss of food sources, both made worse by the Homo sapiens species.

It had been years since I’ve walked the trails of Jean Lafitte, and I certainly am familiar with the look and feel of the bottomland forest. But to experience these ecosystems in a slow, intentional way, using each of my senses to understand the interconnections of the system, is my favorite way to see the space. In the moments when no one was talking, and I wasn’t swatting at pesky mosquitoes, I took in the sights, sounds, and smells of Jean Lafitte. I began to identify particular species that I had seen countless times but never knew the name of. This ability to identify species makes the system come alive.

Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve

New Orleans, Louisiana

September 2020